Rate cuts under review

The speed with which market expectations had moved to price-in rate cuts at the end of 2023 always seemed at odds with the likely reaction function of central banks unless economic activity hit a wall. Arguably, rate expectations today are much closer to a path that resonates with central bankers and the bulk of the forecasting community. We have come a long way from the six rate cuts priced-in at the start of the year to under three currently (Figure 1). Part of the story has been an element of stickiness in the core inflation readings, while the need for cuts has been put back by the continued resilience of the US economy. Both factors will matter in the months ahead but from an asset allocation perspective, we remain of the view that the inflation data is key. This is because so long as inflation remains well behaved, the Fed can cut – if they need to.

Inflation expectations matter

Given the strength of labour markets, a key concern remains the extent to which wage inflation proves difficult to bring down. However, wage growth is cooling, even without a sharp rise in unemployment, arguably because inflation expectations have adjusted back down. A number of economists have argued that because the recent inflationary pulse was predominantly due to a series of supply-side shocks - caused by forces related to the global pandemic and Russia’s invasion of ‘Ukraine - expectations of the path of inflation have not got stuck at high levels. The University of Michigan’s ‘next-year inflation expectations survey’ has fallen sharply in recent months and at 2.9% in March it is at its lowest level since March 2021 (see Figure 2).

Figure 1: US rate cut expectations have been pared back1

Source: Insight and Bloomberg as at 31 March 2024.

Figure 2: University of Michigan 12 month expected inflation2

Source: Insight and Bloomberg as at 31 March 2024.

Europe moves ahead of the US in the race to rate cuts

Expectations are hardening that the European Central Bank (ECB) will deliver a first cut in June. The region stands out as a global weak spot, dragged down by Germany. The economy has been hit hardest by the Russian induced energy shock and by the global slump in manufacturing. By contrast the southern European economies have less manufacturing exposure and have benefited from the revival of travel and tourism in the post pandemic recovery. This means, unlike recent decades, when peripheral European weakness was a pressure for easier policy, it is the core of Europe which is most in need of support.

For now, our assumption is that declining inflationary forces will open a window for easier monetary policy over the summer in the eurozone, the UK and possibly the US. The recent improvement in UK data buys the Bank of England breathing room to assess progress on core inflation. The UK manufacturing PMI moved into expansionary territory in March for the first time since July 2022 while mortgage approvals recently hit a 17-month high, but easing core inflation will allow less restrictive monetary policy.

In the case of the US, however, the prospect of cuts increasingly seems further out, certainly further than the eurozone. As Fed Chairman Powell said in early April, “Given the strength of the economy and progress on inflation so far, we have time to let the incoming data guide our decisions on policy”. A ‘too hot’ scenario is a risk, where activity remains sufficiently strong that inflation becomes problematic and real rates start to breakout to the upside.

Regimes revisited – a constructive outlook ahead

Regular readers may be aware of our regime-based asset allocation framework, which helps us assess likely asset class behaviours in different growth, inflation, and real rate environments. To summarise our investment thesis, since Q4 2023 growth dynamics appear to be stabilising; inflation, whilst above central bank targets, was on its way down; and this in turn has meant the direction of real rates was no longer persistently up. Valuations, and positioning extremes can complicate the picture, but purely from a cyclical standpoint that has historically been a constructive investment backdrop.

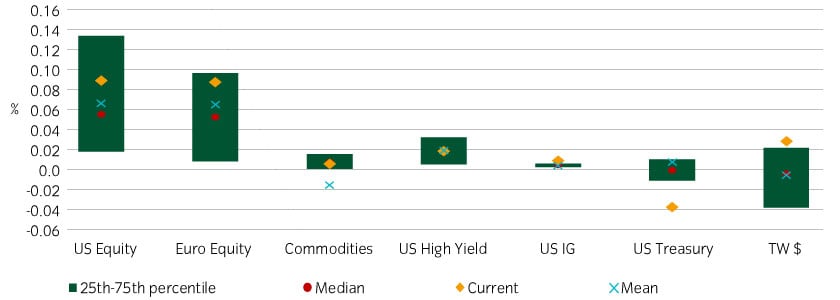

Figure 3 compares the current returns across a range of asset classes with the historic ranges seen in this combination of growth, inflation and real rates over the past 50-years. Developed equity market returns are close to the 75th percentile while the US Treasury and the US dollar are standouts, to the downside and upside respectively.

Figure 3: Asset class performances when growth is ‘rising’, inflation coming down (but above central bank targets) and real rates falling (1972-2024)

Source: Insight and Bloomberg as at 31 March 2024.

Growth backdrop remains supportive

Our expectation is that the growth backdrop will remain supportive. We see a modest deceleration in service activity that will drive a moderation in aggregate US GDP even though manufacturing activity looks set to continue its recovery. Elsewhere, we are seeing signs of stabilisation in the economies that have struggled more over the last year or so. The post pandemic de-synchronization of manufacturing and services and the emergence of rapid growth in new technology (AI) complicate the reading of a ‘normal cycle’.

Real rates are rising but that’s not unusual

As we have noted before, from a historical perspective, relapses in inflation have been more common than one might think. Examples of these ‘premature pauses’ (defined as when the Fed cuts only to subsequently tighten again) occurred in 1973, 1979, 1980 and 1987. The Fed and other central banks will not wish to make a similar mistake so whilst weakness in growth elsewhere may allow policy easing earlier, there is a risk the Fed remains on hold for longer than we currently envisage.

The extent to which this matters from an asset allocation perspective depends on whether there is an upward adjustment in real yields that threatens the growth backdrop. Real yields have moved higher as rate cut expectations have been paired back but for now, the combination of rising (stabilising) growth, inflation edging closer to central banks targets and a modest rise in real rates still paints a constructive cyclical picture.

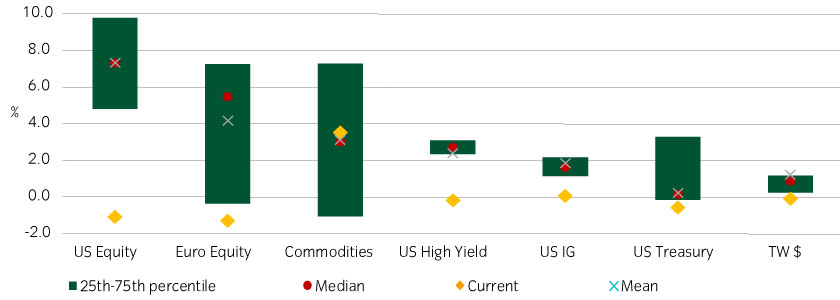

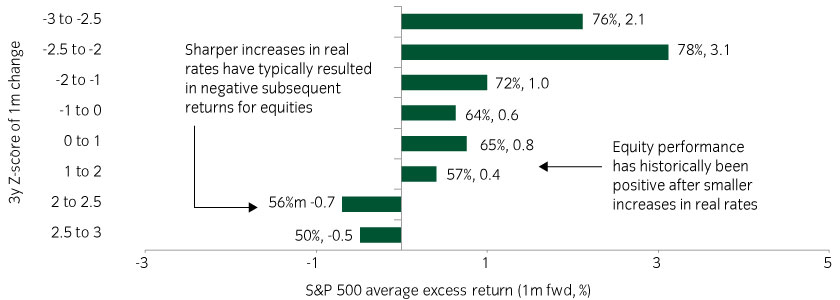

The recent move higher in real yields has caused us to adjust our regime assessment to take this into account. As figure 4 shows, a world of rising growth, falling (but above target inflation) and rising real rates remains a constructive one in which history tells us to remain invested. This shift from a falling real rate environment to a rising real rate one (with the other macro factors remaining unchanged) is not unusual – indeed, it is the most common evolution from an historic perspective. But should inflation start to reaccelerate, or should growth trends relapse, the cyclical picture would deteriorate quickly. If real rates rise sharply then the consequences for risk assets could become more serious, typically resulting in more challenging periods for US equities (see Figure 5).

Figure 4: Asset class performances when growth is ‘rising’, inflation coming down (but above central bank targets) and real rates rising (1972-2024)3

Source: Insight and Bloomberg as at 31 March 2024.

Figure 5: Sharpness of US real rate moves vs US equities performance4

Source: Insight and Bloomberg as at 31 March 2024.

For more thoughts from our multi-asset team click here.

Most read

Global macro, Fixed income

October 2023

Global macro research: Yield-curve inversion – an unreliable recession signal?

Global macro

July 2023

Global macro research: Asset allocation in focus

Global macro

May 2023

Global macro research: Why central banks may struggle to solve the inflation puzzle

Fixed income

August 2024

Ireland

Ireland