By Adrian Grey

|

Geopolitical risks abound, and volatility is likely here to stay

As we consider the investment landscape before us, the word ‘complex’ immediately springs to mind. Central banks have embarked on an aggressive hiking cycle and geopolitical risk is extremely elevated. Many of these geopolitical events create feedback loops for markets. If there are attacks on ships in the Red Sea, costs and inflation rise. Defence spending increases – Japan and Germany are both doubling defence spending over the next few years. This has consequences for fiscal positions and debts. Politics comes into play. Half of the world is going to the polls in some form of election in 2024. India, the most populous country on the planet, has elections in the spring. European elections will be in the summer and of course the US and UK elections towards the end of 2024. All have potential consequences for markets.

This has increased market volatility, and markets are likely to remain volatile for some time yet. The good news is that if markets remain volatile, this is an environment which we would expect to throw up plentiful opportunities to apply our active-management skills. In addition, this is the first time in well over a decade in which investors can generate meaningful returns from income, without having to stray into more esoteric areas of the investment universe.

Perhaps the most important factor of all, however, will be the next step in the rates cycle. Post the global financial crisis central banks took interest rates down to zero and they largely trended sideways for the next decade. After an extremely aggressive hiking cycle through 2022 and 2023, markets are now anticipating a considerable amount of easing in 2024. In our view, markets are now too optimistic, and are likely to face some disappointment.

A higher neutral rate ahead

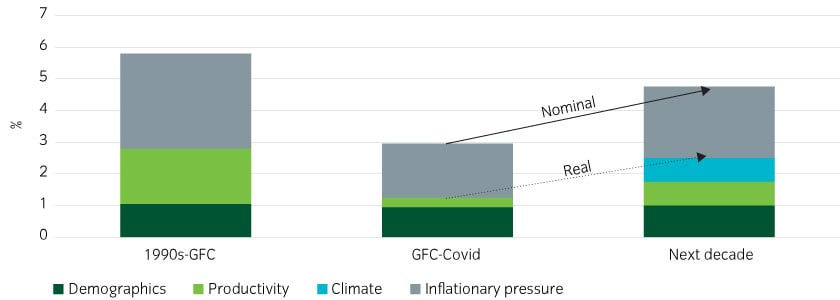

To understand where rates are headed, we need to take a step backward and think about where policy rates are going to settle over the longer term. Figure 1 outlines some research undertaken by BNY Mellon and Insight as to how the neutral rate of interest will evolve, based on four underlying drivers. The neutral rate, or long-term equilibrium interest rate, is the level of real interest rates at which central bank policy is neither stimulating or restricting economic growth.

Figure 1: A higher neutral rate of interest appears likely in the decade ahead

Source: BNYM and Insight Global Macro Research estimates as at 30 November 2023. For illustrative purposes only.

In our view, inflationary pressures will be generally higher going forward, but there are two other factors that we believe are likely to push the neutral level of interest rates upwards:

- Productivity: We’re at the conservative end of opinions, but it’s hard to conclude that artificial intelligence and technology won’t have a positive impact on productivity in the decades ahead.

- Climate: The world is either going to spend a large amount of money in financing the green transition to deal with climate issues or spend a large amount of money to deal with the consequences of not financing that transition. Either way there is going to be a material shift in the savings and investment balance which will likely skew policy rates higher rather than lower.

So, the stage is set for a higher range for interest rates in the decade ahead. Maybe not as high as at the start of the century, but higher than we’ve seen post the global financial crisis.

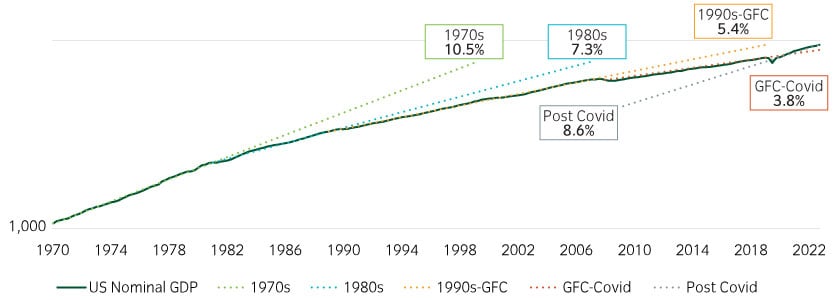

A reacceleration in nominal growth will be a concern for central banks

In the shorter term, there is another factor which is likely weighing on the minds of central bankers. Since the 1970s, nominal growth has been slowing, from an average of 10.5% per annum to just 3.8% per annum in the period between the global financial crisis and the pandemic (see Figure 2). Markets, and humans generally, tend to look at the past as a guide to the future, and there is an assumption that this slowdown will continue. But post the pandemic growth in nominal GDP has reaccelerated to 8.6% per annum. It’s a small sample size, but that has to be an uncomfortable thought for central bankers and may leave them reluctant to rush to cut rates.

Figure 2: US nominal GDP with trendlines – a steady slowdown until recent times

Source: Bloomberg and Insight as at 31 December 2023. Logarithmic scale used.

In our view, markets don’t need aggressive rate cuts to perform well

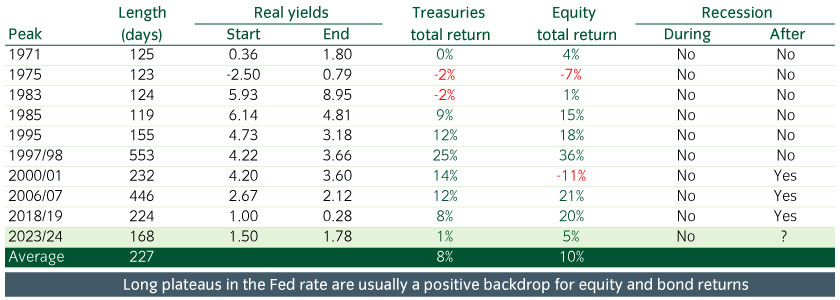

When we look back over the past 50 years or more, episodes where the Fed kept rates on hold for long periods of time have generally been positive for both bonds and equities, with a few notable exceptions (see Figure 3). Episodes where equity markets recorded negative returns included the dot-com bubble, and way back in the 1970s and 1980s where inflation continued to be a problem. Looking at the investment backdrop today, we have the S&P 500 Index close to a record high, and 10-year Treasury yields at around 4%. So, bond markets are able to provide respectable income-driven returns, especially in higher-quality credit. In a scenario where we tip into recession, holding some duration is likely to be very beneficial.

Figure 3: Ten longest extended Fed pauses or plateaus

United Kingdom

United Kingdom