In the face of market turmoil and downgrades to economic forecasts, as well as US corporate executives expressing alarm at the consequences, the Trump administration has started to back away from maximalist economic conflict with the rest of the world all at once.

“Reciprocal” tariffs, for imports from all countries excluding-China, have been suspended for 90 days to allow other economies to negotiate trade deals, but 90 days is a very short time to agree a trade deal even for countries such as Japan where there is a seemingly clear way to rebalance trade deficits (Japan buying more defence and energy from the US). Foreign trade negotiators apparently remain perplexed about what the US actually wants.

In the meantime, many tariffs are in force, and there are likely more to come on products such as pharmaceuticals and semiconductors that are currently exempt but going through a Section 232 process1.

Table 1: US tariffs are driven by a range of motives ($ amounts show value of affected imports)2

|

Negotiating tactic |

Raise revenue |

Reshore production |

Stymie China |

|

|

In force |

|

|

|

|

| Threatened |

|

|

||

| Suspended (for 90 days) |

|

Compared to our previous analysis of the growth impacts, the suspension of the reciprocal tariffs for many countries other than China reduces the impact of the trade channel to some extent. The trade channel impact on China is clearly increased (though it is now well beyond the point of diminishing returns), and the net impact on the US is probably broadly unchanged.

Uncertainty channel impacts on business and consumer confidence will clearly still have an impact, and we are starting to see that coming through in the data.

Key aims of the Trump trade policy remain in place, be it the 10% baseline tariffs to raise revenues (and make business tax cuts permanent), 25% tariffs on strategic sectors the US wants to encourage reshoring of production, or tariffs on China that aim to cripple bilateral trade.

With a 145% tariff on China, but currently only 10% tariff on other countries, third-country re-routing such as via Vietnam will only accelerate, so it is likely that at least some of those currently suspended tariffs are reinstated in time, unless the US can persuade other countries to put their own tariffs on Chinese goods.

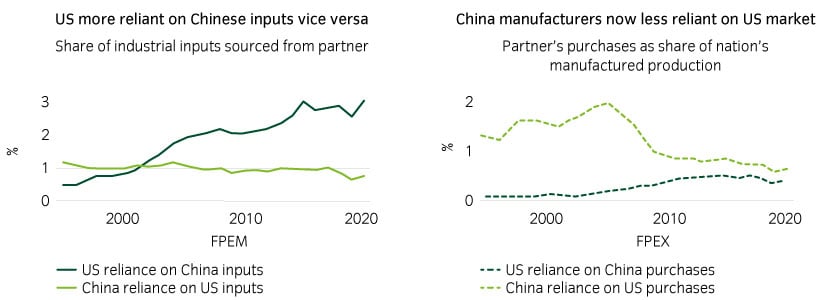

Even if the US restricts the trade war to just China, it is not entirely clear that the US holds all the cards. That US industry is more reliant on Chinese inputs than vice versa is no surprise, but as the chart on the right shows, Chinese manufacturers are not wholly dependent on US purchases and since the financial crisis have seen an increasing share of manufactured products instead going to the domestic market.

Figure 1: The US is more reliant on China for industrial inputs – and Chinese manufacturers are less reliant on the US market3

Given the focus of the trade war between the US and China, it is instructive to consider the other barriers to US-China trade that each side are imposing and the potential consequences.

US non-tariff barriers raised against China

Closing the tariff exemption for small packages

There has been bipartisan agreement in the US that the de minimis exemption such that packages worth less than $800 could enter the US tariff free was overly generous and outdated. The previous Biden administration started the process to remove this exemption, and the Trump administration has completed it. With effect from 1 May de minimis parcels from China and Hong Kong will be subject to either a 120% ad valorem duty or a flat rate per item of $100 (rising to $200 from 1 June).

This will directly challenge the business models of companies reliant on Chinese manufacturing and shipping to the US, including direct-to-consumer Chinese brands such as Shein or Temu, the marketplace platforms of firms such as Amazon and eBay, and many other small firms in China, the US and third-party countries. As with tariffs and other supply shocks, the macro impact is broadly negative for growth at the margin, and inflationary in the US. Trade route re-direction will mitigate this to some extent.

Port fees

Last week the Office of the US Trade Representative published some details of port fees to come into effect from 14 October. Following a consultation these plans have been changed substantially from the initial proposals in February.

- Fee on Chinese ship operators and owners starting at $50 per ton, rising from April 2026 to a plateau of $140 per ton in April 2028.

- For non-Chinese operators/owners using Chinese-built ships, a fee of $18 per ton, again increasing from April 2026 to a plateau of $33 per ton in April 2028. For container ships the fee (if higher than tonnage fee) will be $120 rising to $250 per container.

- For non-US-built ships transporting cars, a fee of $150 per car.

From April 2028 there will also be a restriction on liquid natural gas exports such that at least 1% must be carried by a US-built vessel, rising annually to a plateau of 15% in April 2047.

While these port fees are clearly aimed mostly at Chinese shipping and ship-building, it is not clear how much additional effect they will have given the tariffs already in place on Chinese goods. Scheduled Asia-North America capacity for deployment over the next month has already dropped from 2.44m tons six weeks ago to 2.14m tons, a 12% reduction4. Chinese shipping firms and Chinese-built ships will presumably re-route to non-US destinations where possible, and others will re-route towards the US, so there are definite substitution effects available, but at the margin business should get harder for Chinese shipping firms and fleet with many Chinese built ships, and somewhat easier for other shipping firms. At the margin there will be an upwards effect on inflation, more so for low value-to-weight commodities.

The car transport fee may have the clearest impact, as it is likely to effectively add $150 to the wholesale price of non-North American cars in the US. This seems minimal compared to the overall 25% tariff rate on auto imports.

China non-tariff barriers raised against US

Chinese retaliation is not limited to the 125% counter-tariffs on US goods.

Expanding the Unreliable Entity List and Export Control List

In response to various rounds of US tariffs, China has added 29 US companies to its Unreliable Entities List, and 43 companies to its Export Control List. The Unreliable Entities List includes US-based drone, defence and biotech companies, and restricts import and export activities as well as investment and personnel entry. The Export Control List prohibits exporting items or services for both civil and military applications and include aerospace, logistics and defence firms.

Critical minerals

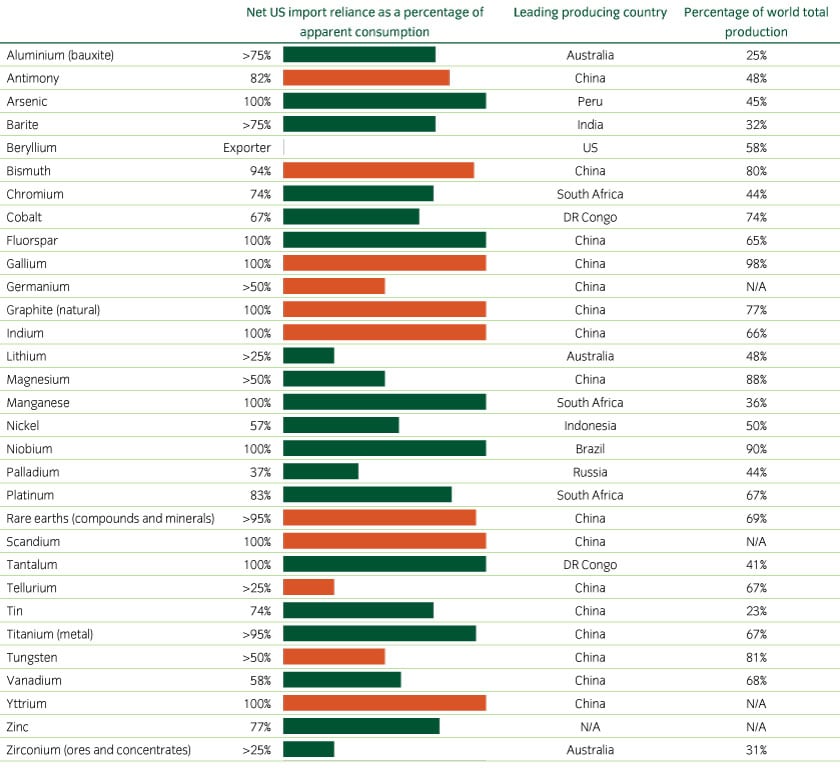

China has also retaliated with export controls on 12 critical minerals so far this year, in addition to gallium, germanium and graphite which were put under export control during the Biden administration in response to semiconductor restrictions.

The table below lists 44 of 50 critical minerals for the US for which production data is available, and highlights those now subject to Chinese export controls. In gallium for example, which is critical for semiconductors and optoelectronic devices for defence, computers and telecom equipment, the US is 100% dependent on imports, and 98% of world production is controlled by China. Potential substitutes for some (but not defence-related) uses include germanium and indium, which are also on China’s Export Control List.

Table 2: Export controls now apply to a range of critical mineral imports to the US (estimated salient critical mineral statistics in 2023; orange bars indicate imports now subject to China export controls)5

Chinese exporters of these minerals now apply for licences from the Chinese Ministry of Commerce. As the US has found in trying to restrict Chinese access to semiconductors, or Russian access to various dual-use goods, such export restrictions can be ineffective unless you go as far as an export ban, which China has not yet done with these critical minerals, but the potential is clearly there.

With export controls US firms, and potentially firms from other Western-allied countries, may need to continuously re-route supply lines to go via third-party countries (as Russia has done via Kazakhstan for example). This will add production delays and extra costs. Fluorspar (feedstock for various chemical processes), titanium (for aerospace, defence, medical and power generation applications in particular) and Vanadium (for steel alloys) look like potential candidates to be added to China’s Export Control List at some point if the trade war escalates.

Should this be escalated to an outright export ban for these minerals there will be a significant supply shock in the world ex-China. Production of many high-tech products would need to be idled, and shortages would start to occur. While alternative sources can be eventually be developed in some cases, this would be over a multi-year timeframe.

United Kingdom

United Kingdom